|

|

John W AdamsHis Impressions of Early South Australia

This version was printed in 1902 by EJ Walker, Balaklava, South Australia. Spelling idiosyncrasies have been retained. Nothing has been changed. Pictures have been added by FRR. One Sunday afternoon we were in Adelaide taking tea with a friend who lived on that acre where Northmore's shops now stand at the corner of Rundle Street [Messrs. John Alfred Northmore & Horace Dean]. There was several houses built then, also a blacksmith's shop. Just before sitting down to tea someone saw a little child fall into a well about 60 ft deep. I ran out with the others and was pulling off my coat as I went, but could not get one arm out. A man got me to hold the handle and he was down the rope quick and got hold of the child.

Several others came and while they drew them up I went for Dr. Woodforde just opposite in Hindley Street. The people around having all their tea kettles boiling a warm bath was soon ready. The doctor examined him and found only a slight scratch on the forehead, and in about 3 days he was running about as though nothing had happened. Another well incident-a man was carrying a bed to his place after dark when he fell into an unfinished well about 30ft deep. As the bed was large enough to fill the mouth of the well it let him down easy and he managed to get on top of it, and in the morning when the men came to work found him unhurt. Before the streets were macadamized they were in a fearful state, bog holes everywhere. When the traffic increased the roads about Adelaide were very bad, especially the south road, in the winter they were all but impassable. Near the Forest Inn a team of bullocks were kept to pull other teams out. A very ludicrous scene happened on the south road one dark night, a very fat gentleman lived in the neighbourhood. As he was walking along the road he slipped into a hole and fell on his back, and he could not get out, but his cries soon brought the neighbours to his assistance. I must go back to tell something of the natives. Whilst on the Park Lands and when we were few in number the natives mustered pretty strong at times. I once saw about 500 assembled on the flat on the North Adelaide side and it was there they held their corroborees and their fights when other tribes visited. We were told that distant tribes about the Murray would come to steal wives for themselves and take them away. On one occasion we saw a tribe come by hill of North Adelaide, marching in Indian file, some were daubed over with some red stuff marked with white stripes. They appeared much surprised to see white men camped there. The women belonging to the tribe about Adelaide came creeping about the huts and wanted us to go and shoot them. They were very much frightened until one of their protectors came and allayed their fears; but they kept about the huts for some time. They held some grand corroborees for a time, but before they left they had some desperate fights. I went to see my old friend Captain Jack after a fight. He had his head broke with a waddy it was a wonder he got over it, as his skull appeared battered very much, I could see his brain. When I went to see him he was surrounded by a large number of his tribe, and one of them with a spear in his hand with a bunch of some kind of shrub tied to the top would walk round them and now and then would look at the wounded man and then would point his spear upward, and would mutter something as though invoking some invisible power; but he got over it at last.

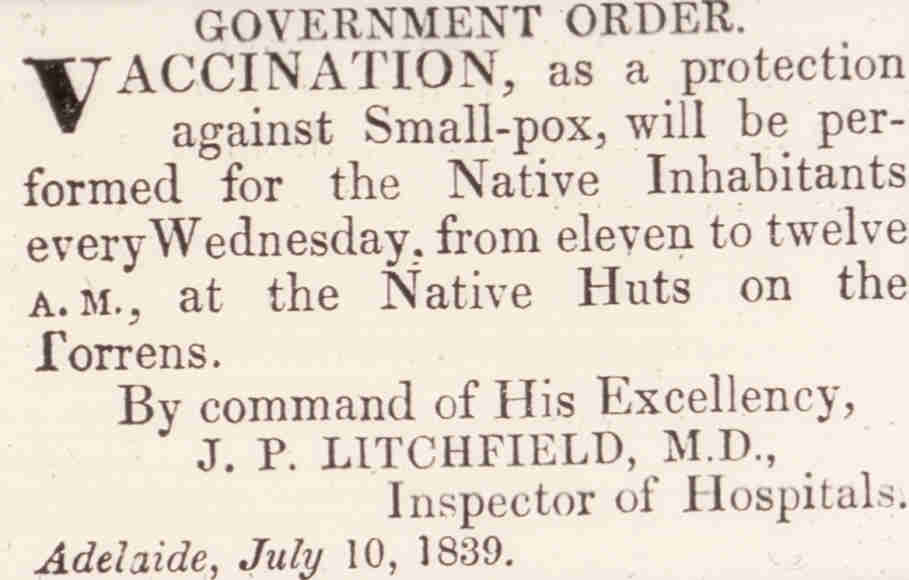

I have never seen them throw their spears in fighting, but their waddies were very often exchanged as they were sitting in groups. After throwing waddies and jabbering for some time the chief, King John, would start up and throw off everything and sieze his spear and stand in an attitude as though he meant to do something, his whole frame quivering as he shook his spear as if in defiance, but not one of the opposite party got up there was quiet for a time. A lot of the women at such times would stand a little distance off with their picanninies at their backs, one of their own tribe would go round to each of them and give them a tap on the head with a stick about 4ft. long enough to break their head and make the blood to flow, and then quietly go and sit down. One mode of their fighting was 2 men would walk side by side with a waddy held by one loosely and trying to make the other take it with their arms around each other, as soon as one of them held it tightly the other would let go and stand out and hold his head down, and the other would give him 3 taps, he would then give the other 3 taps and then sit down. I have seen 2 pass each other running and one of them with a stick they carried give the other a swinging blow at the back of the head and he would fall his whole length, the other would take no notice of him and after a time would go away and sit down. I used to think that their skulls must be very hard to bear such blows without killing them, but I have learnt since that their microscopic eye could see by the motion of the one dealing the blow that he would move so quick that the force of the blow was partly checked. I was rather taken back one day as we were standing in front of our huts, we saw a native women coming. She was dressed in a long coat nicely buttoned up with the fur inside, and her hair was beautifully curled and hung in ringlets, and her appearance showed that some one had partly civilized her. As she was passing I made the observation that she was the prettiest black women I had seen. She looked pleased, and turning her face towards us said: 'Ah, you plenty of gammon, sir'. Finding she could speak English so well we got her to tell us who she was. We found that she was the wife of [William] Walker, of Kangaroo Island, one of the 3 men who had been left there for a number of years by a whaling ship, the other men's names were Cronk and Cooper, and these men were exceedingly useful to the first settlers as they knew the language of the different tribes and often prevented quarrels, and was interpreters for us. One day myself and another borrowed the natives kangaroo dogs for a hunt and a boy who I suppose was about 15 went with us. We hunted where Enfield now is and was then known as the pine forest, a favourite place for Kangaroos. We saw 15 whilst we were out, the dogs caught one, part of which we took home. They killed others but the scrub was so dense we could not find them. We knew that by the dogs being cut so much. It was usual to give the forequarter to the natives. We cut it up and pointed to the boy to take his share, but he would not carry it. We slung our part on a stick and carried it home on our shoulders, and being a warm day found it as much as we could do. It weighed about 90lbs. The lad that went with us was about the only boy about that age in the Adelaide tribe, all that generation appears to have been taken off by smallpox, all the survivors were very much marked, we learnt this from the white men. After many years, and we had been living at Ball's Creek sometime, as I was passing the window to go into the house I heard a native's voice say there's 'Addamy' and was saluted on entering by a shake of the hand by a native who was no other than the boy, now a man, who went with us on our hunting excursion. After the lapse of years he had not forgotten me. We sat down for a yarn about old times. Among other things he related the circumstances of our Kangaroo hunt. He told me his part was too heavy and it was too hot to carry so long a way. He told me some of his people was living about the Coorong and invited me to come and live with him for a week, a month, if I liked, plenty Kangaroo there, plenty duck, plenty fish, plenty everything. On a Sunday morning as the folk were wending their way to church, Trinity Church was not then finished, only in part, we saw 2 natives come from the river. Their appearance was different from any I had seen. They were smeared over with something and a quantity of fine white down covered nearly all their bodies, their heads were dressed with feathers and they had in their hands a small dart about 18 inches long with feathers stuck on at one end. They came up Morphett Street and appeared to be looking for something. They tripped it along so light-stepping on tip toe, pointing their darts up the street and looking up to the sky all the time. I afterwards learnt that they were the rain makers of the tribe. Whilst living on the Park Lands the natives supplied me with fire wood, they would take a tomahawk and go up a gum tree and cut the limbs off. The way they got up was surprising, they would gag a piece of bark out just enough to place their toe in, at first with a waddy, but after a while they got a short piece of iron and pointed, they would cling to the one hand clasping the tree, a great toe in the hole in the bark, and go up to the top. That was the way the Park Lands became denuded of its trees, all limbs cut off by the natives and as the immigrants began to increase the white man felled the butts and then grubbed the roots, until all the trees disappeared. Some of the natives were cunning thieves. We began storekeeping on the Park Lands, and one time we had a lot of potatoes shot out in a corner of the store in a heap. We caught one of them standing by the heap while another was drawing our attention to something, and with his toes lifted the potatoes up behind and hand them to another just outside. We found they had a lot about them when we searched them, When the baker came with bread some of them was sure to be there, and we often missed a loaf very mysteriously. We paid the blacks for their wood, &c., mostly in rice and sugar. They got a piece of tobacco from all smokers, it was not safe to pay them until they had done what they agreed to do, and as soon as they got paid they would make a fire and boil the rice, and after eating it would wrap themselves up and beat their breast with a sing-song until they were fast asleep. On one occasion we were alarmed in the night by a lot of them throwing firebrands about near a hut, and the report was they intended to burn the huts, it turned out afterwards that one of them had a grievance, as a man who shot a quail, by accident a shot struck a native at a distance, and he thought the man shot at him. We turned out about 22 strong armed with guns, swords, bayonets, &c., and marched round them, but we had no occasion to use the powder. After that we formed a watch, 2 started at one end of our huts and partrolled all round our encampment, 2 others would start from another point and pass each other about midway with the cry of 'alls well,' and this we did for some time, we went armed, but the natives did not trouble us any more of a night. There was a man the worse for liquor came to the store, he bought a piece of pork, it was near sundown, he lived at North Adelaide. He got across the river, for next morning he was found murdered by the natives. They had stabbed him with a small bone they carry through a hole in their nose. The only wound was in the heart. Until he was opened by the doctor we could see only a small drop of blood. He must have died without pain as he was found laying with his legs crossed and a slight twitch of the muscles of the mouth. The immigrants were going out in search of the murderer armed, but the Governor interfered, there was not a native to be seen about for sometime, but the murderer was discovered some time after, and was hung, he was supposed to be the same fellow who hit a Mr. Barnet, of Hindmarsh, on the head whilst bathing, and was thought to have drowned, his little girl who was a little way off minding his clothes saw the fellow go to the river with a waddy in his hand. Some of them were very expert in throwing the spear, they would often show us by throwing the reed at one another, they would have a shield of bark and catch the reed as it was flying, and not one of them ever got hit by them however straight they were thrown at them. Two of the Sydney blacks who came here showed us how they threw the boomerang, that is about one of their most dangerous weapons. They throw it first to strike the ground, it then rises up and forms almost a circle in its course and comes back to them with great force. (The principle of the boomerang struck Sir Thomas Mitchell, of Sydney, that it was a propelling power and a steamer was fitted up with one instead of the screw, it was tried at the measured mile at Portsmouth, England, and found to propel the steamer 12 knots an hour, this is from the English news.)

Whilst living on South Road a lot of the natives passed on their way to Adelaide from Encounter Bay where they were taught by the late Mr. Newland. They wanted a drink and in their usual way some of the boys asked 'what name you' and on telling them my name was Adams, they looked at me in a strange way and then asked me where was Eve. I understood them so pointed to the house. They were anxious to see Eve and wished me to bring her out. When I brought out my wife they looked at her and said 'that's not Eve, that's Adamey's lubra.' One day the natives came near us carrying the dead lubra of King John to their burying-ground on the section of Mr. Wright's. They had been carrying her about to their camping places for about a fortnight. King John asked me to go and see her buried. I went with 2 others, on arriving at the place the men who carried her went to a certain spot and after some ceremony they took her for about 3 yards and walked backward and forwards 3 times, and then laid the body down. They then sat down in groups, made their fires, ate, and smoked their pipes. After a while the women got up and went near the body and began to lament, and falling on the body uttering most piercing cries, on getting up we saw the tears streaming down their persons. They then spread out and collected bundles of dry grass, the men got a quantity of bark and one began to dig the grave with a spade I had lent them. They made a small hole at first and when they got down about a foot undermine it, and when we looked in it appeared like a large round pot, but we did not stop to see the closing ceremony. They brought the spade back battered up, and between them drank three 12-gallon buckets of water. I went to see the grave the next day, they had left a small fire at one end and bark was piled up like a roof over the grave, and all was very neatly done, and for a fortnight after one of them would come every evening to make up the fire. About the first of January, 183-, myself and wife, Nicholson and wife, Breaker and wife, had the use of a dray to go into the hills. We reached a spot just at the place you turn down to Crafers Inn, and there camped for dinner I have many times passed the stumps of stringy bark we sat on since then. Returning we were very much in want of water. The track was then only a bullock dray mark, and in some places we made fresh tracks. We used to go up and down Green's hill before any roads were surveyed. We were opposite the spot where Eagle on the Hill now is, and the question was put who would volunteer to go down the hillside to try for water, it was the opinion of the whole party that water could be got in the gully below. Accordingly myself, Breaker, and Mrs. Nicholson volunteered. We struck as straight down as we could on the spur. The difficulty of descent kept us a little way apart, and I happened to be the middle one and arrived at the bottom first and found a small stream about as wide as my hand and about a yard or so from the edge of the rock, where it fell over. I shouted out I had found water. Mrs. Nicholson came next and then Breaker joined us. He had gone about 20 yards from us and we saw afterwards if he had gone a little way further he must have fallen down a precipice. As soon as we were all together we tried to make out what sort of place we had got to, the bushes were very thick about, and the bare rock where we were standing was not above 3 or 4 yards wide. We crept to the edge of the rock and found it was a waterfall. To us it appeared a great depth and we were thankful that neither of us had gone near enough to fall over. We could see by the trees that the gully below was a great depth, we there and then named it Adams' waterfall. Breaker by climbing got over to a projecting rock, and we named that Breaker's castle. We could not at first understand the peculiar moaning sound we heard, but found it to proceed from the sheoaks by the slight current of air passing through them. We penetrated a little way up the gully but found it very rough, but there was plenty of water among the broken rocks. After quenching our thirst we ascended to our party and our faces told by the streaks of white we had a rough time of it, but we were thankful for the supply of water we had brought up. A little time after I had told some friends of our journey, and a party of three besides myself went up to the fall, for such it was. On arriving near one of our party being rather fat declared he could go no further. He laid down on the slope of the hill holding on by a wattle, his brother and a friend got down, and they wished to have a momento of the place. There was a grass tree growing a little below, and us two held on to his feet while he reached the centre piece, and at the time I write I have no doubt but that he has it in his possession, he told me not many years since he still had it. The other gathered a bunch of flowers. We returned to our friend we had left half way down still laying on his back. He declared if half Australia was given him he could not go down. We returned home much pleased with our journey, and although I have passed the fall scores of times and have stopped at the Eagle on the Hill, I have never paid a visit to the fall. Soon after Mr. Hutchinson walked up the gully from the plains and came to the falls, which he described in the paper sometime after, he computed its height to be about a hundred feet. In the early days of the Colony we were often very short of the common necessaries of life, especially flour and meat, and some years passed before we could supply ourselves, as everything had to be imported from the older colonies, a ship brought some sheep from Van Dieman's Land, and on her arrival everybody was anxious to get some mutton, although at a very high price. One of our party being at the bay when she arrived bought a fore quarter at 2s. 6d. per lb and brought it up to the camp, and when cooked a hungry man might have eaten all at one meal. Some of the sheep landed was said to have been drowned but that made no difference, it was mutton for all that. Were it not for the cockatoos and parrots we should have been badly off, we could get a little Kangaroo at times from the natives. When we could get beef it was 1s. per lb., and it was a scramble to get it at that. Flour was the great tax upon us, it rose in price that it was almost impossible to procure it at 80 to 100 pounds a ton, but that did not last long, but quite long enough combined with other things to crush nearly all the merchants and storekeepers, and a sad state of things followed. Some few began to grow wheat as an experiment, and after a year or so we had plenty and to spare. I remember the first acre I grew on the South Road. I got the land ploughed after a good rain about the middle of February, and on the 26th I sowed it. It came up well but the dry weather after scorched it, and I thought it had all gone dead, but the occasional showers and the winter rain setting in about the end of April it recovered, and at harvest time we reaped it, and it turned out about 20 bushels of fine wheat. The first seed wheat I bought was 20s. a bushel. In a new colony we had to learn everything. I adopted the old English plan, reaped it and laid it in grip and turned it over to dry in the orthodox manner, and when I tried to tie it I could not as the straw was too brittle, and I had to get rope yarn for the purpose, and I was not the only one who had to get experience. In looking back it often provoked a smile to see the way we blundered on for a year or two. We hacked our wheat in with a broad hoe and then dragged a harrow over it. I had only about an acre and a half out of 20 that were clear, and the grabbing took a deal of time, one tree was so large it took a man a fortnight to grub and cut up. I remember Ridley's first machine, how it went into the field in the morning and reaped and cleaned the wheat and took it to the mill to be ground, and the next morning it was on the table in the shape of rolls for breakfast.

The principle of the machine was the same, but the machine of today is worked very different; the first machine had a long lever behind to steer it and keep it into the wheat, and it was considered a wonderful contrivance. I think at some time a monument will be erected to the memory of John Ridley for the benefit conferred on the farmers of South Australia, it must have occupied a lot of his time to construct the first, he was a perservering man. I knew him well, and I had the honor to accommodate him and his family the first night of his arrival at Hindmarsh. It was a pity his first machine was not kept. Among all our trials and difficulties the Sunday was kept as a day of rest from the first. The service was conducted by the Rev. C. B. Howard, sometimes under the shade of a gum tree, as was the case at Glenelg, and in a hut for some little time until Trinity Church was sufficiently forward for the purpose. The first services performed at Adelaide on the Sunday was in a reed hut by the side of the track leading from the Port to Adelaide, near where the cattle yards now are, and the bell was put up on a pole on the rising ground near the corner of Adelaide: people lived in the hut but on Sundays they packed up their household goods in a corner, the congregation had to sit on boxes or anything they could get, none of us was troubled with much furniture at that time, and what we had was of a very primitive description. All the different sects used to join, and after Mr. Stow's people built a chapple at Hindmarsh, Mr. Howard would preach there on part of the day. On a Sunday when he was preaching in the hut it came on to rain so heavy, and began to drop on him and the book; as I was acting clerk to him I slipped up an umbrella behind him to shield him and the book before him, he objected to it, and said he would take his share with the congregation, these and similar acts endeared him to everyone. When he got his stock of books up he made me a present of the Bible and Prayer Book that he used on the voyage out and up to that time. Soon people began to spread around Adelaide, and we went to live in the black forest on the great south road, and we assisted in getting up a church, at first a frame work covered with broad palings covered with shingle, and afterwards part of the present structure. The first was built on an acre nearer the cross roads. One morning it was surrounded with water from the heavy rains. A lot of us had to dig a trench to lead the water off. One Sunday as Mr. Farrell was preaching one of the heaviest thunderstorms we had witnessed came on, accompanied with hail and rain so that we could not hear him; he lengthened out his discourse at intervals for near an hour. During the storm a cow was struck dead with the lightening on a section about a half a mile from the church, and at Happy Valley a pair of bullocks in yoke was struck dead. St. Mary's Church was the first suburban church that was erected. After living on the south road for a number of years we removed to the country and it was seldom that we visited the old place. When I had occasion to pass, the words of the Psalmist would recur to my memory-if I forgot, &c., &c. Our last visit was in 1876, and on going round the yard we read on the tomb stones the names of our fellow worshippers in years gone by, awaking some pleasant memories, mixed with pain and thankfulness that we were yet spared. ***

If you would like to find out more,

|