|

A Town with a Past. Passing on to Blackfellows' Creek (which does not deserve a better name) we met Mr. Rodney Matheson, of Nilpena Station, who was about to start shearing. A long stay was made at the substantially built station of Beltana. The town of course has lost much of its old-time dash and life, but situated on the edge of a gum creek (Warrioota) on the other side of a hill which shuts out a view of it from the railway station, it looks as picturesque as ever (as far as northern towns go).

The renowned Beltana Pastoral Companys' run, once carrying nearly 100.000 sheep, gave it vitality, but overstocking, drought, and vermin, told their own tale and the pioneers of the district would not recognise the country now. It was originally held by the late Mr. John Haimes as the Mount Deception and Pertuba runs. Then it passed into the possession of the late Sir Thomas Elder and was afterwards floated into the Beltana Pastoral Company. This country has since been enclosed with a vermin-proof fence by a board which embraces several Stations. Beltana is the junction of three important pastoral and mining roads. The Sliding Rock mine is 14 miles distant and it once supported a brewery, two hotels and two stores.

Warrioota Creek |

Crows Eggs Dont Hatch Chickens. A 20 mi!e spin brings us to Leighs Creek, said to have been named after George Leigh, a stockman, who was located for some years at Patsy Springs, an outstation of Moolooloo. One of the little community to meet the train was Mr. J.W. Duck, a very old pioneer, who is still hale and hearty. The appalling monotony of life in these far northern townships appeals to the visitor as he notes the unanimous manner in which the residents assemble to take part in the inestimable boon of train arrival.

The bi-weekly 10-minutes commune with the outer world just saves the situation. I asked a friend who was complaining of the soul-killing nature of his existence whether the Sunday services did not relieve the monotony, and he replied that the opportunity of public worship occurred only about once a month and that on the last occasion he attended the preacher held forth on: the homely truth that 'crows eggs don't hatch chickens.' That may be so but judging from the great numbers of crows in the far north, it looks as though chickens and every other kind of bird are hatching the croakers.

A few copper mines in the neighbourhood of Leigh's Creek (Now called Copley) are being worked on a small scale, and slipping along another six miles the poppet heads of the coal mine show up in the gloom to remind one of unrealised expectations. It seems a thousand pities that this once-promising industry still lies dormant, considering the immense body of fuel that the operations proved to exist in the mine. At a depth of only 150 ft. a seam 51 ft. thick was encountered, but the bore revealed coal of a belter quality blacker and more glossy at 1400 ft. There is a sample of it in the Adelaide School of Mines. The company is still intact. The only house in the vicinity is the empty managers residence, which has iron nailed up at all the windows and doors.

Leigh Creek open cut 1951. SLSA B20303 |

Lyndhurst is a siding very convenient for the Murnpeowie Station, belonging to the Beltana Pastoral Company and then comes Farina, originally known as the Government Gums. The town is half a mile from the railway station, which appeared a busy one. It taps a large share of the Queensland pastoral trade and at the time the yards were full of Springvale cattle and Haddon Downs and Nappa Marrie wool. A few days before 100 camels had been sent away to Western Australia.

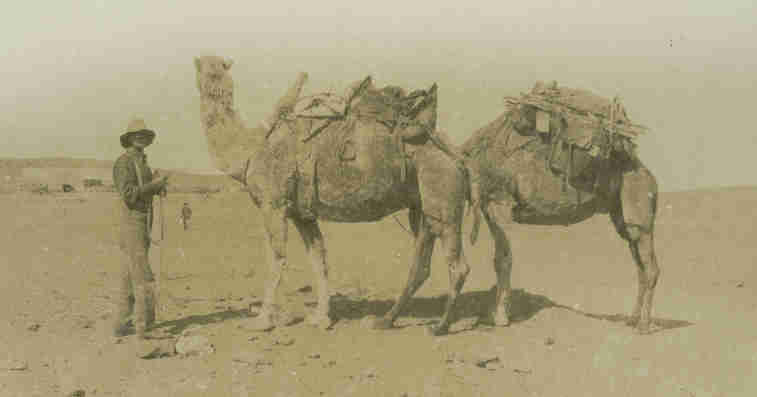

Mount Lyndhurst Station. SLSA B71685/6b |

There is also at Farina a great heap of wire netting for the newly formed Lake Torrens East Vermin District, which will embrace 3,800 miles of country, including Witchelina, Myrtle Springs, Ediacara, Mulgaria, Beltana, Kallioota, Wallerbedina, Moralana, Warrakimbo, Lake Torrens, Nilpena, and Marrachowie Stations. All these things imparted a lively air to Farina, but the town generally has languished, in sympathy with the pastoral industry. One of the Ragless Brothers, of Witchelina met the train here and took in hand a wool classer.

An Old-time Encounter. Between Farina and Hergott Springs an astonishing number of bush graves exist. The stage, one of 33 miles, was a most treacherous one in the early days. Unwary stockmen would drink at the salty Bulloo Springs near Hergott, and perish on the dry way to Farina. Many of the graves are now completely blown over and to locate them would be an impossibility. Wirrawilla and Mundowdna Stations separate Farina from Hergott.

Mundowdna was taken up many years ago by Mr. Thomas Matthews, of South Rhine, and then by Messrs. Woodforde & Debney who stocked it with sheep and cattle and had a sensational encounter with niggers from Coopers Creek, who stuck up the station. An inquiry was held and it was found that the measures taken by the whites for their own preservation were justifiable. Among those who conducted the enquiry was Mr. H. Swan the retired Stipendiary Magistrate who then occupied Angorichina Station. Mundowdna is now held by the Messrs. Whyte.

Hergott Springs. The train drew in at Hergott Springs, 441 miles from Adelaide, at 10 pm nearly two hours late, but supper that ought to have been tea at Mr. R. C. Barnes' comfortably conducted hotel had not suffered by the delay and the waitress was remarkably good tempered. She said she was used to it. The temperature was not far above freezing point, and yet in the summer this is one of the hottest places where records are kept. The showplace here is the State date plantation, into which the artesian bore, 342 ft deep, flows.

The Conservator of Forests is very hopeful concerning the future of the plantation, but the photographs of picturesque corners which he has included in his annual imports sadly flatter the place. The lack of uniformity in the growth of the palms detracts from the appearance of the plantation, and many dead tips added to the drawback. Still, the experiment of growing dates, although a costly one may be reckoned a success. Plenty of the palms are well established. Locally produced dates are sold in Hergott at 6d. a lb but so far neither in quality nor in price can they compete with the imported article.

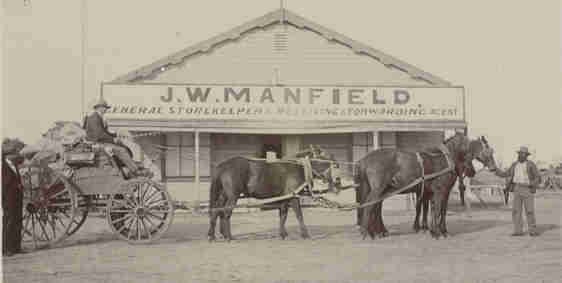

The railway authorities appeared determined to keep Hergott Springs dark, for having been landed there at 10 p.m., travellers were required to be aboard again at 6 a.m. The company, however, were congenial, and their hampers even better. The passengers included the Hon. J. Lewis, M.L.C. Dr. Chenery, of Port Augusta, who is a great believer in the far north as a sanatorium, Mr. Fred Turner, of Quorn, Mr. R. G. Allen, of Nilpena Station. Mr. J. W. Manfield, who has stores at Farina, Hergott, Oodnadatta and lnnamincka, and later on Mr. J. Paxton, manager of Stuart's Creek Station.

One of Manfield's stores. SLSA B 71545/43 |

The time table was observed to the minute right through on this day, which was not bad, considering that a fortnight's business had to be transacted at every calling place. The sun was up by the time Callanna was reached. The pastoral property in this neighbourhood was taken up originally by Sgt Burt, who found the Welcome Springs, and was stocked with sheep by Messrs. Levi and Braund. The sheep did well until the early sixties, when the drought reduced their numbers from 7,000 to 1,400, and then the big rain of 1866 drowned all of them except three.

What shocking extremes! The sheep would be a perfect animal up here if it had the thirst-resistance of a camel, and the web feet of a duck. The only incident at Alberrie Creek was the picking up of a shivering goat for Stuart's Creek Station. It seemed like carting cattle to Newcastle Waters to send a goat to Stuart's Creek, but there was the fact. Further, it appeared that half-starvation was ahead of the goat, but the manager averred that the feed was splendid "outback." Everybody said that. Evidently the railway has followed the line of least sustenance.

Passing Wergowerangerilinna which is merely mentioned to annoy the reader who would attempt to pronounce the name the Hermit Hill comes into sight. This was trigged by Mr. Babbage, the explorer, and the trig is still there. It overlooks the famous Finniss Springs. The pastoral country was early occupied by Mr. J. Weatherstone, later on by the proprietors of Lake Hope Station, and more recently by the trustees of the late Mr. J.H. Angas. It is nothing like the Finniss on the Victor Harbour line, but a combination of the two classes of country would make a very desirable spot. Sand drift was badly in evidence.

Waterhole Squatters. At Bopeechee there was time to read a placard, in which the proprietors of Stuart's Creek Station (Willowie Pastoral Company) offer a reward of 100 for the apprehension of cattle stealers. The Crown Point people are offering a reward for the same thing. The depredations of what are known as clay pan or waterhole squatters are a serious menace to pastoralists in the unfenced country of the interior. Taking up a ridiculously small area of pasture, these men raid the outskirts of a run and gather in young unbranded cattle and horses. The rent of 1/ or 2/6 a square mile is, of course, nothing to them.

They start pastoral operations with a few head of stock. Wonderful fecundity these animals must possess, for in two years a couple of mares will multiply into perhaps 60 head! The hunt for clean skins is always going on, and seems to be a fairly profitable business, while the task of sheeting home any crime is an exceedingly difficult one. One man is said to have borrowed a nigger's shirt in order that he might go into a township in decency, yet the Government has no compunction about allotting country to such individuals. The clay pan squatters are worse than the wild dogs in the cattle country, for if the dingoes do wipe out a few calves, they at least keep the rabbits down, and thus preserve the pasture.

Sad Facts about the Angora. The virtues of the Angora goat have been so loudly sounded in this State that a few words concerning his short comings ought to be accepted without complaint. He is getting pretty common in the interior, and is beginning to be found out in many things that could never be charged against the ordinary, common specimen of the ruminant that pulls a go-cart about for the benefit of the young folk, and undergoes a course of training for the Eight Hours Sports. The subject arose on the train through the shipment of the shivering goat referred to. The advent of the animal created a spirited discussion among the pastoral passengers, from which it was apparent that the Angora has not given the greatest satisfaction in this country.

Said one authority 'The Angora goat can not compare with the merino sheep in dry country, or even with the common species of his own breed. The merino will see out anything else on legs. I have seen sheep fat where the longhaired goats have gone under, and have had to feed Angoras on compressed fodder while the sheep have been able to shift for themselves'. This emphatic opinion met with general endorsement from others qualified to speak on the subject. However, it is not the fault of the poor Angora that he was not specially designed to defy droughts, but something really discreditable was urged against the breed in regard to the rearing of their young.

There are few animals more regardless of their offspring. In the endeavour to bring up the kids in the way they should go, pastoralists have had to tie them to their mothers' legs. They breed well, a lambing of 200 per cent being a common occurrence, but the problem is how to sustain the young. Where would the Angola goat industry be but for the black gins? I had an ample opportunity to observe the usefulness of the blacks in this direction.

When yarded up the Angora mothers, even when in splendid condition themselves, spend most of their time in repelling the advances of the kids. They sweep the little creatures away with a hind leg, or boost them unkindly with the head. Then the native women come along and take the young goats in hand. They gather up a kid, collar the mother by the legs, throw her down, and squat on her while the youngster steals a milky pick-me-up. The goat industry is certainly an appropriate adjunct to squatting pursuits.

Sometimes a majestic looking billy sneaks up at the back of a gin and sends her sprawling along the yard. He is just as bad a father as the other is a mother. The encounters between lubras and billies are highly diverting, but would be more in place inside a circus than on a respectably conducted station property. The gins squeal worse than an indifferently stuck pig, and their jabber sounds suspiciously like unparliamentary language.

When the goats are turned out of the yard to graze the greatest difficulty is experienced in getting some of them to leave their young. The lamentation of the mothers is almost heartrending, and the shrill cries of the kids help to make bedlam at the head station. But it is all a sham. The older goats had simply been engaged in kicking their offspring in the yard, and the seemingly affectionate parting is all humbug. The gins for some reason of their own do not sit on every neglectful mother. They nurse some of the little ones in another way.

A weedy kid is picked out and put on the bottle. It is intensely amusing to see them administering milk through the stem of an old clay pipe bound with rag that acts as a stopper to the bottle. One holds the kid and the other works the feeding bottle, and the four-legged waif eagerly embraces the artificial method of suckling, whereby they thrive wonderfully. But what a mockery all this is on the Angora goat industry, which, unless the mothers wake up to their parental responsibilities, threatens to die with the fast-decaying race of Australian blacks.

None of the gins mothering the flock in question has children of her own, and the lubras give all their devotion to the goats. Their love for them is remarkable. But it would never pay to engage white labour to nurse Angora kids, and the average man would have to be hard pressed for work before he would lend himself out to foster neglected goats. It is a wonder that pastoralists allow themselves to be troubled with such a petty industry.

No doubt one of the reasons is that the Angora may be profitably barbered twice a year. They are fitably barbered twice a year. There are other drawbacks to the breed. Besides lacking in maternal affection their milk and the butter made from it are not so good as the product of the ordinary go-cart goat, and certainly not equal to that of the cow, although the taste may easily be acquired. The person with sensitive nostrils would find a still greater grievance.

It is a well-known fact that horses and cattle when grazing are loath to follow in the wake of the goats, and one only has to stand beside an Angora yard to guess why. The pretty creatures, so haughty and dignified in comparison with their more common relations, are attended by a vile and undying odour when herded together. Woe to the inhabitants of a head station where an Angora flock is daily yarded. Use of the coarsest language would not exaggerate the unpleasantness of the goat zephyrs which ooze through doors, windows, and chinks, and cleave to everything like whelks to a rock.

Particularly offensive is it on a warm day or after a shower of rain.

Please God the Angoras will beat the black gins in the race to the grave, or the interior of Australia will lose its great reputation for a salubrious, lung-healing climate. The consumptive might as well pitch his camp on the nearest rubbish tip as introduce himself to a head station where the smeliful Angora is established. With the goat yard humming and with the flies and mosquitoes in tune, a summer in the interior is to be dreaded. But give the Angora his dues, his mutton is delicious.

If you would like to find out more,

please go

to home page for more information.

Thank you for visiting South Australian History,

We hope you enjoy your stay and find the information useful.

This site has been designed and is maintained by FRR.

|